The Actual Factual Truth About The History of Yoga

This is a deep dive into what history really says about yoga. Perhaps you break this content up to digest in parts rather than all at once. I designed it to be a live document so as new information arises, this page will be updated.

Yoga’s story is rich and layered. Surprisingly enough.. it is still being debated. We celebrate it as a 5,000-year-old practice rooted in ancient wisdom and that’s partly true but the real history isn’t a solidly packaged, lineage of poses from prehistory to Instagram. So let’s unpack it.

A statue of Sage Patanjali (aka Gonardiya or Gonikaputra)

Yoga Did Not Start With Downward Dog

Most of us think of yoga as stretching. Or we think about hot and sweaty yoga classes. But ancient yoga did not begin with a focus on asanas (poses). In fact, the word “yoga” comes from the Sanskrit root yuj, meaning: to yoke, to unite, or to integrate. This is an indication to focus on mind-body integration.

The history of Yoga takes us back to the northern India region. Early references to yoga are philosophical and spiritual and they emphasize the importance of meditation, breath control and inner awareness. This was long before physical postures were systematized. Bending into a complicated shape in a yoga class is a modern (primarily Western) expression of yoga. It is not a reflection of the earliest form.

The Earliest Hints of Yoga Are Archaeological

Many archaeologists point to the Indus Valley Civilization (~3300–1300 BCE) as an anchor for yogic practices. A famous artifact called the Pashupati seal was found in Mohenjo-Daro and it shows a seated figure in a posture resembling padmasana (lotus pose).

The Pashupati seal

But here’s the nuance: There are no written records proving yoga existed as a system at that time; only suggestive imagery. And since the Indus script isn’t fully deciphered, these interpretations are merely an educated theory. There are indeed hints but we do not have a clear roadmap from ancient seals to modern classes.

The Bhagavad Gita, The Vedas & The Upanishads Hold The First Textual Mentions

The Rigveda (1500–1200 BCE), one of the oldest known texts in the world, contains early references to the root yuj. It does not reference it as a pose, but as a spiritual practice focused on union. The Vedic Period (1500–800 BCE) shows yoga as a concept, not a practice of poses. The focus was on ritual, chanting, breath and spiritual discipline.

Later, the Upanishads (800–200 BCE) dive deeper into meditation, breath control (pranayama) and consciousness which is the heart of yogic philosophy. It frames the practices designed for self-realization and liberation. These texts didn’t list sequences of stretches. There wasn’t any imagery of yoga poses. They taught a way of being… a way to be human. So there was a shift from being ritualistic to more of an inner quest of curiosity. The intention was moksha (liberation). This is where yoga becomes introspective and philosophical.

The Bhagavad Gita (dated roughly 200 BCE–200 CE) is one of the most famous texts referencing yogic scripture. The words yoga and yogi frequently occurs in the Gita. Almost every chapter is named after a form of yoga: Karma Yoga (Yoga of Action), Jnana Yoga (Yoga of Knowledge), Bhakti Yoga (Yoga of Devotion) and Dhyana Yoga (Meditation). The Gita does not reject the Vedas, but it demotes ritual as the primary path to liberation. The Gita accepts Upanishadic philosophy while also saying that you don’t need to leave the world to wake up. This was huge because instead of renunciation-only spirituality, the Gita introduces liberation through engagement, not escape. Yoga becomes the method for living wisely inside of society not something exclusively for monks, ascetics, rishis and forest sages.

An ascetic performing a yoga pose at an event in India

Patanjali Didn’t Invent Yoga But He Codified It

Around 200 BCE to 200 CE, the sage Patanjali compiled the Yoga Sutras, which became a foundational framework for what we now call classical yoga. He didn’t create yoga from scratch but he essentially organized existing spiritual practices into a coherent philosophy described through 196 aphorisms. This included the famous Eight Limbs of Yoga (ethical life, breath-work, meditation, etc.) There wasn’t a mention of headstands or complex yoga poses here either. Asanas (yoga postures) were thought of as a seat for meditation.

The Post-Classical or Medieval Period (~500–1500 CE) is where Hatha Yoga was developed. Texts like the Hatha Yoga Pradipika referenced. This is were the introduction of more physical techniques came into play like mudras (sacred hand gestures) and bandhas (yogic "locks" that involve specific muscular contractions to direct prana (life force energy) within the body. The purpose? It was to prepare the body for long meditation and spiritual awakening. These postures were not taught in group classes and not designed for general wellness.

Tantra Yoga is one of the most misunderstood traditions in yogic history. Historically, Tantra emerged in India around 500–900 CE as a radical spiritual movement that challenged rigid, renunciate-only paths to liberation. Rather than rejecting the body or the world, Tantra taught that everything (including the body, breath, sound and emotion) could be a doorway to awakening. The central goal was expanded consciousness; it was not solely about pleasure. Tantric philosophy reframed the body as sacred. This was revolutionary in its time.

For Centuries, Yoga Was Mostly Meditation & Philosophy

From about 500 BCE through the early Common Era, yoga lived mainly in spiritual discourse and philosophical communities. These were often within Hindu, Jain and Buddhist traditions. Yoga is not a religion and was practiced by people of various faiths. Asanas were practiced, but they were supports for meditation not the main attraction.

Now there’s the Colonial Period (1800s) that matters more than most people realize. British colonial rule in India suppressed many indigenous practices. This is when Indian teachers began reframing yoga as “scientific” and “physical”. It was repackaged in a way that Western audiences can digest.

Modern Yoga Took Shape From the 20th Century

Here’s where yoga history really pivoted. The flowing, dynamic asana-focused yoga most of us know began to take shape in the 1900s. Early 20th-century teachers like Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, B.K.S. Iyengar and others helped shape this modern practice. It is debated that some modern postures may have been influenced by other physical culture systems from Europe and India such as gymnastics, wrestling drills and calisthenics blending with traditional Hatha Yoga.

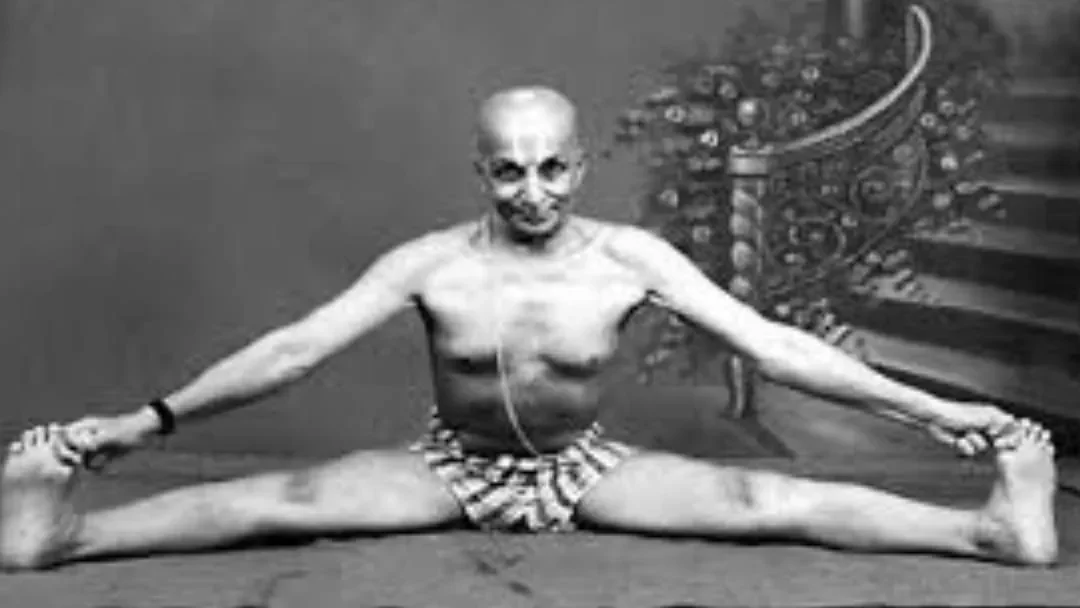

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya seated in a yoga pose

Yoga became physical, secular and commercialized. A ton of culture appropriation and bastardization followed from here. It was still yoga but it definitely evolved. Krishnamacharya is considered as The Grandfather of Modern Yoga and many Western yoga practices are traced back to his students. He taught yoga to be adaptable to the student no matter their age or physical ability. Young, old, athletic or injured; he did his best to make it accessible.

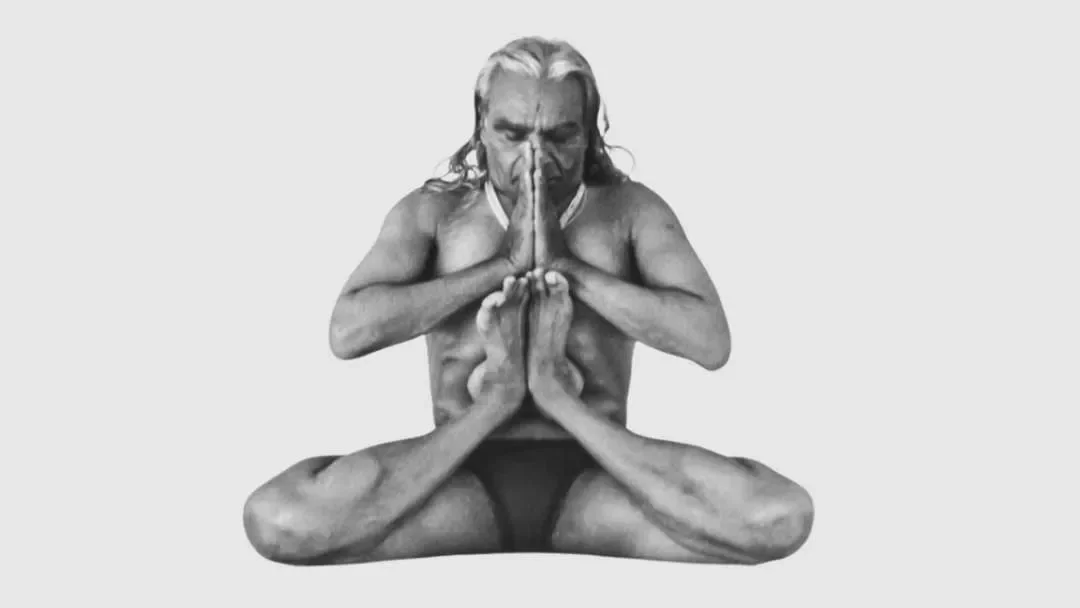

B.K.S. Iyengar, or Bellur Krishnamacharya Sundararaja Iyengar, founded Iyengar Yoga in the 1930s and made it about alignment and props. He took a therapeutic and methodical approach, designing it for longevity and accessibility. He focused on anatomy and weaved spiritual discipline into the mix.

BKS Iyengar (Bellur Krishnamacharya Sundararaja Iyengar) seated in a yoga pose.

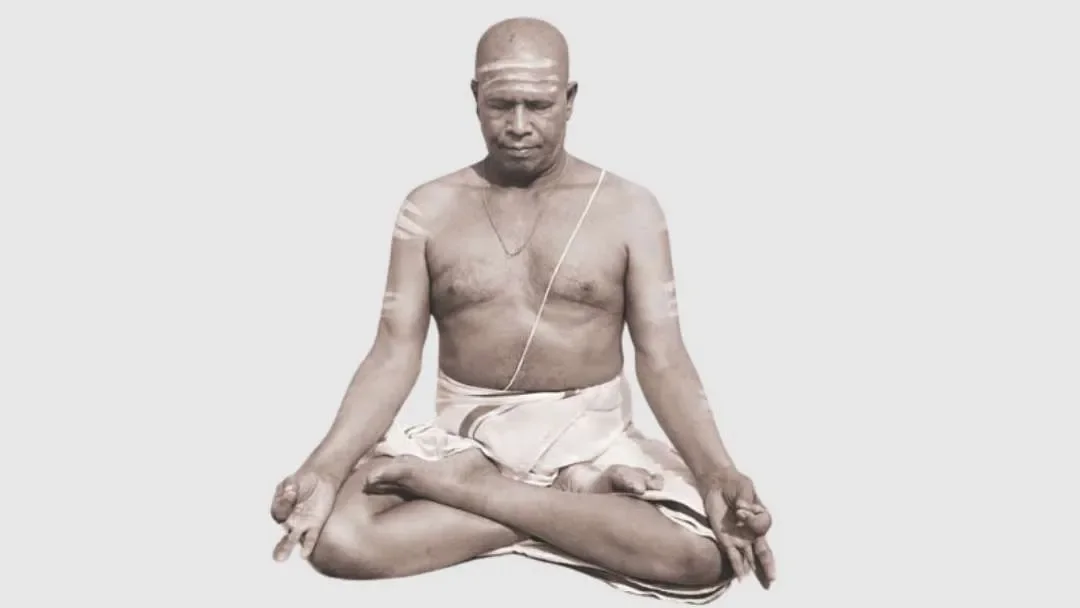

K. Pattabhi Jois is credited as the founder of Ashtanga Yoga which was designed in the 1930s too. The breath-to-movement synchronization was his idea. It was designed to be physically rigorous and complex. Vinyasa is a method that was borrowed from Ashtanga’s linking of breath + movement. This might be the most popularized expression of yoga to date.

A photo of Krishna Pattabhi-Jois seated in yoga pose

Hot Yoga blew up in the west and it was seen as a physical practice more than anything. A strict series of 26 poses and 2 breathing techniques was the recipe. The man who founded it in the 1960s was later accused of very harmful behavior so we won’t even mention his name.

Yin, Restorative and Trauma-Informed Yoga draw heavily from modern anatomy, neuroscience, and psychology. They are deeply aligned with yoga’s original goal: nervous system regulation and awareness. The intention is ancient. The application is modern. These practices were developed between the 1950s and 1970s.

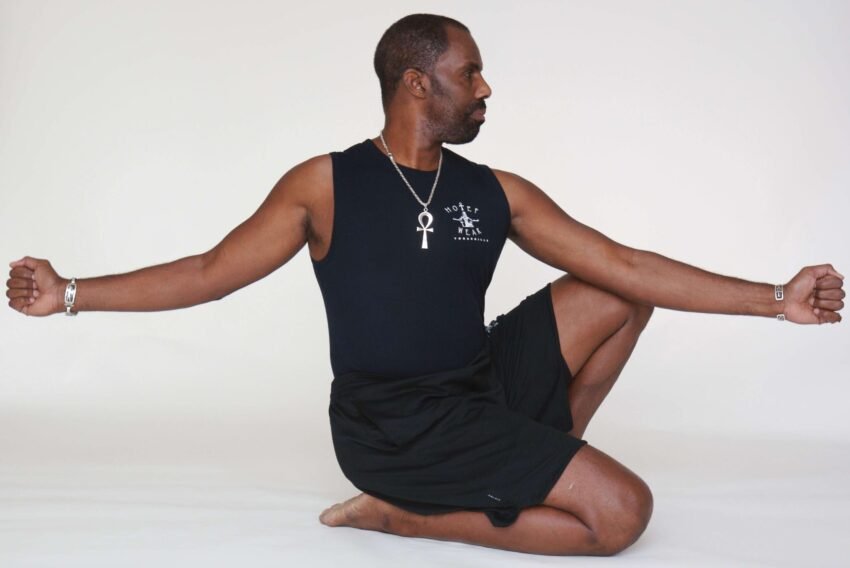

Kemetic Yoga refers to a system of postures, breathwork and spiritual philosophy drawn from ancient Egyptian (Kemet) civilization. The practice was founded by Yirser RA Hotep in the 1970s. The postures are angular and symmetrical and were not designed for flexibility or fitness, but for energetic alignment, moral discipline (Ma’at), and spiritual ascension.

Yirser RA Hotep seated in a yoga pose

There’s No Single Linear Timeline And That’s Okay

A Yoga show in Kolkata in 2012

Historians generally agree that yoga has ancient roots in Indian spiritual traditions. They agree that the idea of union (mind–body–spirit) is much older than any specific physical routine. And while many like to trace a direct, unbroken lineage back to prehistoric sages, it seems nearly impossible to say that it was been unchanged over 5,000 years.

Indian school children participate in a yoga session at a school in Chennai. (Photo: Arun Sankar/AFP)

There are a few women of ancient yoga that I’d like to mention such as Gargi Vachaknavi, Akka Mahadevi and Anandamayi Ma. I’m still researching more yoginis (female term for yogi) but I discovered an article, How Ancient Indian Women Shaped Yoga, that I’ll be diving into soon.

Indian yoga enthusiasts perform yoga on International Yoga Day in Amritsar on June 21, 2015. (AFP: Narinder Nanu)

So What’s the Real Truth?

Yoga is ancient but not in one form. Its spiritual philosophy goes back thousands of years; its systematized breath and meditation techniques go back millennia; but the dynamic posture-based yoga so many of us practice grew up in the last century.

Yoga is a living tradition. It evolves. It adapts. And just like us, it grows wiser with time. There are plenty of other ancient derivatives of the practice and even more modern derivatives that I did not mention in depth. Lots of information to digest.

As I stated in the beginning, this is a living document that will be updated as more information presents itself. Please share your thoughts in the comments and let’s keep the conversations going.